How much sleep does your child need?

I spoke on Monday to the Year 10 cohort, as part of our fortnightly Flex program. My topic this time was “Sleep Matters” and my focus was on helping the students to understand the vital role that adequate sleep plays in good health. I alerted the Year 10s to some alarming statistics:

- – 70% of Australian teens are chronically sleepy

- – Australian teens are the third-most sleep deprived in the world

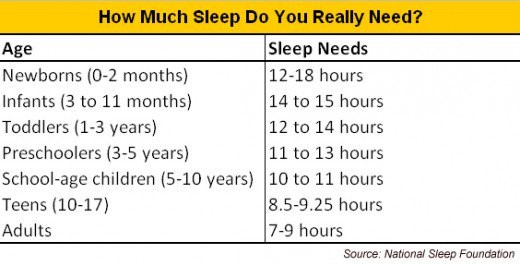

Of course, that begs the question: What does it mean to be “sleep deprived? How much sleep is enough? Medical science suggests the following:

Interested to know about our school, I asked the students to complete a brief survey for me, and here are the results:

|

Year 10 Sleep Survey (hours/night) n=128 |

||||||||||

| Average sleep hours | 5 or less | 5 ½ | 6 | 6 ½ | 7 | 7 ½ | 8 | 8 ½ | 9 | 9 ½ or more |

| % of students | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 13 | 15 | 27 | 13 | 8 | 10 |

If we compare these two tables, and accept that 8 ½ hours or more is needed during the teenage years, then the conclusion to be drawn from this data is that more than two-thirds of our students in Year 10 self-report that they aren’t getting enough sleep.

Should we be concerned about this data? I believe so. As I shared with the students, the benefits of adequate sleep include better concentration and improved decision-making, better memory and recall, increased creativity and a stronger immune system. Conversely, sleep deprivation results in impaired classroom learning, reduced sport performance, emotional fragility, poor food choices and a reduced capacity to deal with stress. Especially worrying is the research that shows that the combination of acute stress and poor sleep in a teenager who is genetically vulnerable to a mood disorder (including anxiety and depression) will bring out or trigger the mood disorder.

It won’t surprise you to hear that one of the contributors to sleep deprivation in adolescents is time spent on screens in the evening. Quite apart from the time this might take away from sleep time, gaming and messaging result in the release of dopamine and adrenaline, which make your child feel more alert (rather than sleepy). Compounding this is the blue light emitted by screens, which inhibits production of the sleep hormone, melatonin. Interested to learn about the screen habits of our students, I asked in the survey whether they had an internet-connected device in their bedroom at night. 84 % reported that they do.

Australia’s leading Adolescent Sleep Physician is Dr Chris Seton, from the Westmead Children’s Hospital. Dr Seton talks about two “red flag” questions to ask, to determine whether a child is sleep deprived. So, of course, I asked them –

- Do you tend to have a big sleep-in on either Saturday, Sunday or both (in a vain attempt to catch up on your sleep-deficit)

Yes – 63% No – 37%

- Do you find it very difficult to get up in the morning (on school days)?

Yes – 57% No 43%

Again, the conclusion I draw from these results is that perhaps two-thirds of the 128 students who responded to my survey may be suffering from sleep deprivation.

My objective in speaking with the students (and of sharing this summary with you) was to highlight the benefits of adequate sleep and the problems associated with not getting enough sleep. Of all the factors which may contribute to academic and sporting success, as well as mental health and wellbeing, sleep is probably the factor over which students and their parents have most control. I would really encourage you to have a conversation with your child(ren). If they are not currently getting enough sleep (and remember, 9 hours is recommended), then together you need to develop strategies to change this.

If you have serious concerns, our counsellors may be able to help. Alternatively, you may like to follow up on the program developed by Dr Seton – http://www.sleepshack.com.au/

Mr Nigel Grant

Executive Director of Teaching & Learning

Photo by Ivan Obolensky from Pexels